It’s well-known that stock investments are just business investments. When people purchase a piece of property, such as a farm, a rental property, or a private business like a restaurant, they tend to view them as business investments: they measure their investment results based on how much such a business makes along the time. Seldom do they keep checking their business’s valuation quotes monthly, let alone daily. Over time, they might need to exit such a business and only then do they start to quote and value their properties as a wholesale price.

This is not what happens in public stock investing: with the advent of daily, hourly, and even stock price quotes in seconds, the investors’ wealth or fortune fluctuates wildly based on these real-time stock quotes. Unfortunately, such an appraisal is not accurate and can swing to both extremes.

It’s thus advocated by many successful investors such as Ben Graham and Warren Buffett that investors should focus on the underlying business of a stock, ignore short-term prices, and invest just like an investor in a private market (a private investor such as a start-up investor, private business investor or a rental property investor). If the underlying business performs well and your purchase price is right (cheap enough), you’ll make money.

Index fund investing removes individual stock/company risk by investing in hundreds, or even thousands, of companies. It’s common that you hear/learn in financial media on long-term investing: buying and holding an index fund for a long time to achieve its long-term returns. However, it’s less common to hear that investing in an index fund is not much more different than investing in an individual company, except in this case, your “individual” company is a “conglomerate” that consists of a collection of businesses from its underlying stock components.

In this article, we look at S&P 500 from a business investment angle (this is also called “fundamental investing,” but we prefer calling it “business investment”). In the next newsletter, we will look at US Real Estate Investment Trusts (REITs).

Long-term S&P 500 Return on Equity

One of the most important metrics to evaluate a business is Return on Equity (ROE). Equity is the actual business value owned by a shareholder. It’s the total asset value of the business minus its liability. ROE measures the percentage return the owners make in a period of time. In general, if you possess a business that can return more than 10% out of your equity annually, you’d consider it to be reasonably good business. An annual 15% ROE would be considered as very good.

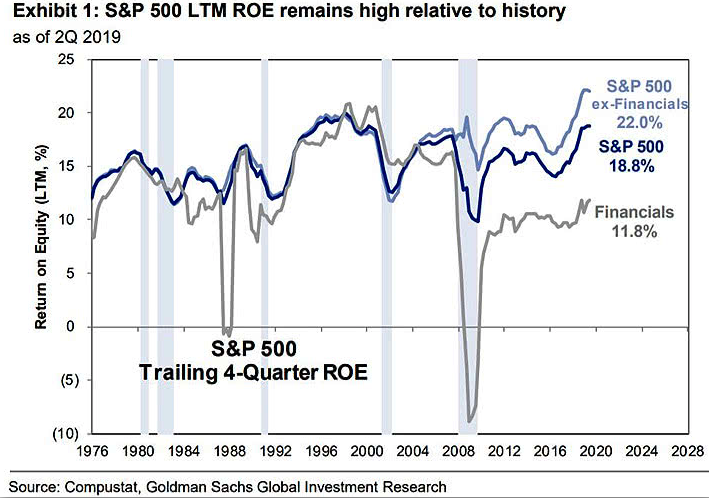

Well, it turns out that if you are an owner of an S&P 500 index fund such as SPY, VOO, or VFINX, you actually own a very good business. The following recent chart from Goldman Sachs shows that S&P LTM (Last Twelve-Month) ROE has been around 15% since 1976:

In fact, the lowest ROE since 1976 was around 10% in the 2008-2009 period. So, even at its worst, it still had a very reasonably good ROE.

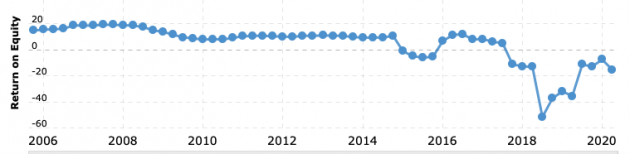

This is compared with General Electric’s (GE) ROE since 2006:

GE’s ROE has been around 10% since 2009 and then started to drop precipitously from 2015. Remember, GE was used to be a bellwether for US businesses for a long time.

S&P 500 Profit Margin

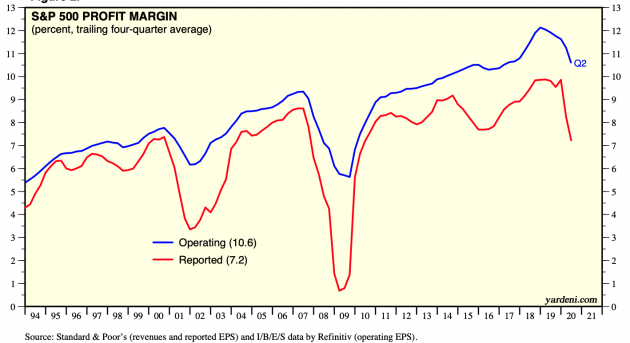

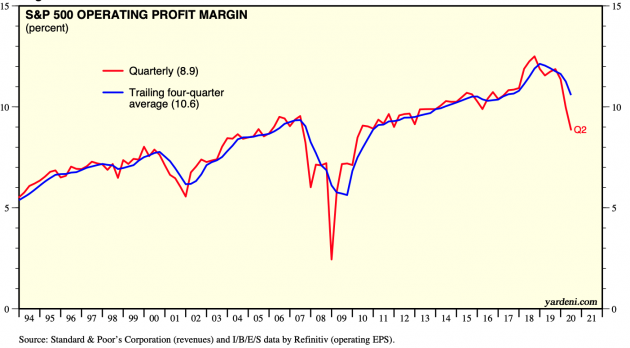

The other important metric is the profit margin of a business. The following two charts show the history of the S&P 500’s profit margin and operating profit margin:

(Courtesy of Yardeni Research)

Since 1994, S&P 500 aggregate operating profit margins and profit margins (trailing four quarters) has never been negative even in the severe financial crisis in 2008 and the 2000s tech bubble-induced bear market. This is remarkable, as many individual companies were in the red in those times.

Embedded filtering mechanism in an index

However rudimentary an index “conglomerate” might seem to be, capitalization-weighted stock market indexes actually possess some embedded filters that can weed out bad businesses over time.

First, only reasonably good businesses can have an IPO to a public stock market. To further stay in the public market, they also need to maintain reasonable performance. Otherwise, they will be delisted. This serves as a natural filtration.

Secondly, indexes such as the S&P 500 have certain stringent criteria to include stock. You might think this is a natural acquisition. For example, the S&P 500 index committee meets once a month and reveals its methodology once a year to adjust the index (weights, inclusion and exclusion etc.). See the S&P index methodology document here.

Finally, the capitalization-weighting approach in these indexes is actually a good enough capital allocator for these “businesses”: the better the underlying businesses, the better their individual stock prices and that translates more weights to these “good” businesses (not always, but in the long term, stock prices do converge to reflect their fundamental businesses) in an index.

Stellar long-term returns

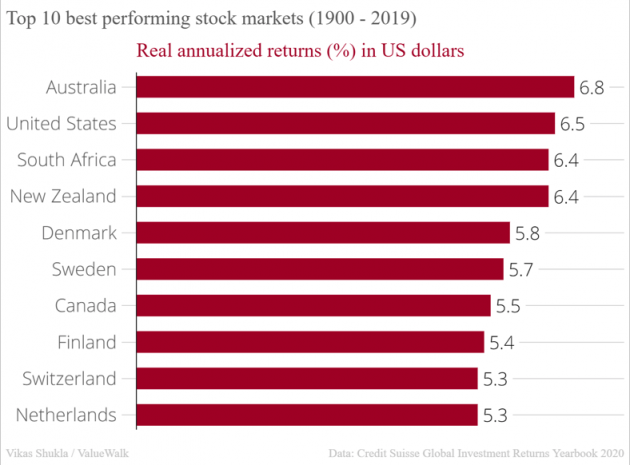

Essentially, owning an S&P 500 index fund is like owning a good and relatively stable business. It should reward its owners in a long term. This is reflected in its long-term stock index returns. The following chart shows the long-term stock market returns (total returns including price and dividend reinvested):

(Source: Long-term stock market returns since 1900 – Credit Suisse)

Real returns are excessive returns over inflation. S&P 500 index doesn’t represent the whole US stock market. But it actually delivered slightly better returns in the long term.

Not many businesses are able to outperform the S&P 500 index business even in terms of business metrics such as ROE, profit margins, and profit growth. In fact, Warren Buffett has used the S&P 500 index as Berkshire Hathaway’s (BRK.B) benchmark, and it hasn’t been easy for Berkshire to outperform (before the 2018 Berkshire Hathaway Shareholder Letter, his letter used to include per share book value to compare with S&P 500).

To summarize, investing in a good broad base stock index fund is actually like owning a reasonably good business. You just need to make sure the price is right when you purchase it.

Of course, we need to remind readers that good long-term returns do not necessarily mean that returns in short term or even relatively long term (10 years or so) are guaranteed to be good. In fact, we have seen the S&P 500 index price can fluctuate wildly. Furthermore, just like any stock price, an index can be very overvalued at times too. This is especially true at the moment: given how overvalued the S&P 500 index is, it’s very likely that the index’s total return will be flat or so for the next 10 years. Investors need to keep this in mind.

Disclosure: I am/we are long SPY. I wrote this article myself, and it expresses my own opinions. I am not receiving compensation for it (other than from Seeking Alpha). I have no business relationship with any company whose stock is mentioned in this article.

from WordPress https://ift.tt/35gsXzu

via IFTTT

0 Comments